Team Interactions

In Autonomous Team Structure, we discussed how self-sufficient teams plan, implement, and deliver their respective software features independently. To enhance their productivity, we established three types of internal supporting teams and outlined their functions. This chapter highlights distinct approaches to how these software teams work together effectively.

Conway's Law

"Any organization that designs a system (defined broadly) will produce a design whose structure is a copy of the organization's communication structure."

- Melvin E. Conway

"If you have four groups working on a compiler, you'll get a 4-pass compiler."

- Eric S. Raymond

"The architecture of the system gets cemented in the forms of the teams that develop it."

- Ruth Malan

"Someone who claims to be an [Software] architect needs both technical and social skills. They also need a remit that is broader than pure technology - they need to have a say in business strategies, organizational structures, and personnel issues."

- Allan Kelly

Conway's Law decrees that every software architecture ultimately mirrors the structure and communication practices of the team working on the software. It emphasizes the misconception that organizational structure and software architecture can be separated. No matter how strongly we mandate a certain architecture, the software structure will ultimately converge towards the department structure. This reality has been an inconvenience for software companies that organize their departments by discipline and enforce conservative reporting hierarchies.

Modern software companies leverage Conway's Law to their advantage. A strategy called the Inverse Conway Maneuver demands that we design our organization around the product, not the other way around. First, we design the software, and then we position autonomous teams in line with the software's modules. Assigning people and teams according to their software contributions reduces friction in software delivery.

Alas, software architecture goes beyond identifying modules and components. We define the responsibilities and boundaries of each part and build programming interfaces for each module. We mirror these patterns in our inter-team dynamics. When autonomous teams interact, we ensure distinct ownership and accountability of domains through established interaction patterns.

Interaction Forms

While we incentivize inter-team communication, teams cannot work together in an organization-wide free-for-all. Operating effectively within a team has less impact when operating beyond it becomes burdensome. To get work done, we define sensible and productive interactions between teams. Depending on team dynamics, these differ in approach, frequency, and duration.

As mentioned in Autonomous Team Structure, we refer to the insights of Matthew Skelton and Manuel Pais, authors of Team Topologies (I highly recommend this book and encourage readers to further explore their website and Youtube videos.). Skelton and Pais identified three common forms of interaction between teams.

Collaboration

A collaboration phase is characterized by a high degree of discovery. When a difficult problem within a vertical team prompts us to spin off an Enabling Team or Complicated-Subsystem Team, close collaboration between the teams is essential to understand and solve the problem. When we design new systems across multiple domains, several vertical teams work together to solve problems that span disciplines.

During inter-team collaboration, team members participate in pair programming and (virtual) whiteboarding sessions. In the early stages of collaboration, teams communicate frequently and through all available channels. Yet, collaboration is a finite phase. Prolonged communication leads to increased administrative and social overhead, as problem-solving turns into multidisciplinary, serendipity-driven busy work.

Conway's Law counsels us that tight collaboration over time leads to interdependent software services lacking well-defined responsibilities. After establishing foundational success criteria, we cap the amount of communication between teams and refocus our efforts on solving our domain problems. Depending on the problem, we either shield the team from the work they collaborated on or establish them as the first consumer of an X-as-a-Service.

X-as-a-Service

As indicated by the titular software strategy, vertical teams consume the output of an X-as-a-Service interaction strategy. Whether our teams consume libraries from a Complicated-Subsystem Team or rely on the functionality of an internal platform, this interaction form is unidirectional. It provides distinct clarity of ownership between the teams.

Mature X-as-a-Service communication is founded on strong documentation and self-service functionality. Aside from dedicated support for Day 0 and Day 1 tasks, this interaction form requires little in-person assistance. As is the case with public software, the quality of the interaction improves with predictable deliveries, consistent APIs, and a focus on a positive developer experience.

Facilitating

A facilitating team actively supports a vertical team in tasks other than directly working on the main software systems. These teams provide expertise to enhance aspects of the product development cycle. For example, facilitating teams may accelerate software development by setting up skeleton systems for continuous delivery tools and demonstrating how to extend and configure the team's setup.

When teams tackle a problem that requires different skills than previous problems, facilitating teams fulfill an educational role by teaching the team a new language, framework, or design pattern. For example, due to organic growth, our team decides to move from a synchronous architecture to an event-driven architecture. A facilitating expert demonstrates the opportunities and challenges this decision brings and shares successful approaches and popular tooling for the transition.

Besides facilitating technical problems, we establish these teams to mediate inter-team conflict, bridge political gaps, or gather company insights via holistic evaluations. Just like Collaboration, Facilitation is a temporary state. Once the facilitating action is completed, the vertical team can function fully autonomously.

Putting it All Together

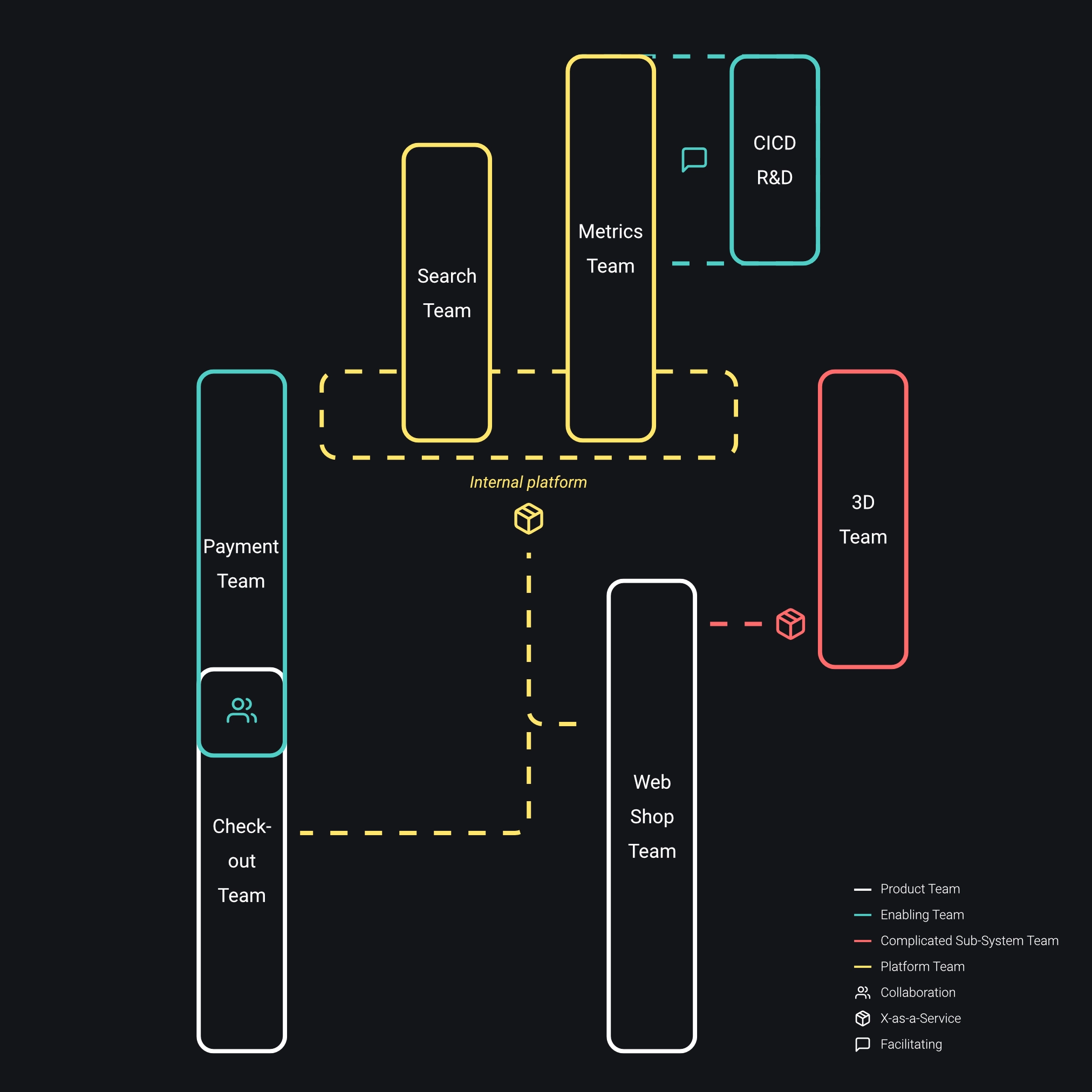

We visualize our team topology by connecting autonomous teams via the interactions discussed above. Employing the Inverse Conway Maneuver, we partition our teams and interactions by our software architecture. The following image demonstrates an example of the interaction modes.

As an image offers limited space, we confine ourselves to two product teams in our example. In reality, our product teams far outnumber our supporting teams. The checkout team and the web shop team release features to our consumer-facing product. These autonomous teams own the entire development lifecycle of their respective domains, from customer feedback to design, code, testing, and delivery.

As the responsibility of global payment systems exceeds the checkout team's resources, we create a dedicated team for regional compliance of payments. Initially, the team collaborates meticulously with the checkout team to establish requirements and services for financial transactions. Over time, the payment team develops a set of libraries or creates a payment platform and offers their solution via an X-as-a-Service interaction.

The 3D rendering team has already matured into this state. Our web shop team consumes the 3D team's sophisticated WebGL rendering libraries to display products in an additional dimension. The interaction patterns between these two teams have shifted from personal discussions to communicating via the provided documentation of the API.

The image includes two vertical platform teams, respectively working on product search capabilities and self-service metrics tools. These teams provide their services via an internal platform, accessible to all teams across the company. With a growing number of teams consuming these services, the platform teams reduce computational costs by building high-performance solutions and reduce communication overhead by providing a solid and transparent developer experience.

Our CI/CD research team spent the last months evaluating tools and strategies for advanced testing practices. Facilitating our metrics team, the research team presents and validates its findings in a low-risk internal environment. Once the metrics team reaches self-reliance with the new practices, the research team facilitates the next vertical team.

Recommendation

In Team Topologies, IT consultants Matthew Skelton and Manuel Pais share secrets of successful team patterns and interactions to help product, technology, and engineering leaders design high-impact team-of-teams organizations. Engineering Collaboration covers some high-level concepts of Team Topologies.

For additional details and information, I highly recommend you check out the book and more at teamtopologies.com.

Communicating via Team Interactions

Limiting ourselves to three interaction patterns allows us to develop, share, and continuously improve our communication strategies for each form of interaction.

For example, we consolidate practices, presentations, and prose for X-as-a-Service documentation. Shared tools and standards help our engineers find relevant documentation and reduce the friction when onboarding new teams. Official support channels for X-as-a-Service teams ensure we identify recurring problems and allocate time for dedicated support personnel.

During substantial changes across our organization, we sequentially facilitate a large number of teams. After every iteration, we reflect and document how we may improve our approach for future teams. Facilitating teams become more efficient through sheer practice. We update our materials and demonstrations after every session and ensure all teams have access to the latest versions.

Frameworks for successful collaboration patterns support coherent and orderly interactions between teams. By recommending the frequency and structure of collaboration meetings, we avoid chaotic multi-team free-for-alls. While we encourage direct messages between teams and team members, we ensure they are not the forum where decisions are made.

However, we can't (and don't want to) control all communication within our company. Designing team interactions creates blueprints for exactly that - inter-team interactions. Individual contributors will always need to send direct messages to each other across the organization, whether for quick clarifications, asking for advice, or venting about work. These back channels bypass bureaucratic processes and help teams get work done faster.

Why we mandate collaboration methods

"Technologies and organizations should be redesigned to intermittently isolate people from each other's work for the best collective performance in solving complex problems."

- Etha Bernstain, Jesse Shore, and David Lazer

"Intermittent collaboration found better solutions than constant interaction."

- Bernstein and colleagues

"The roots of Toyota's success lie not in its organizational structures but in developing capability and habits in its people."

- Mike Rother

When joining teams via interaction modes, we ensure their communication emphasizes trust and mutual respect. A popular tool to prime our teams for success is Promise Theory. Originally developed by computer scientist Mark Burgess, this framework defines our inter-team interactions by promises rather than obligations.

Contracts are the most common example of interacting via obligations. When foreign entities cooperate, a neutral third party outlines the responsibilities of each entity in a written contract. The corporate world demands that we interact with caution and distrust. Without precise language, any failure in personnel, personality, or politics can have disastrous consequences for our organization.

However, within our organization, we trust our teams implicitly. Our peers want to see us succeed. Even if a partner team fails to deliver on a promise, instead of assigning blame, we resolve the issue together. Failure rarely arises from incompetence or malevolence but rather from a lack of resources or inconsistent communication.

Instead of requesting obligations, we present our objectives to our partner team. This ensures that the team with domain expertise has all the necessary information and the freedom to work on an optimal solution. The resulting output often outperforms any requirements we could have come up with. Ultimately, this trust-by-default approach ensures the right people are solving the right problems in the right way.

Over time, the topological view of our organization clarifies what our teams work on and who they deliver to. Tracking these sociotechnical dependencies enables us to evolve our teams' responsibilities. We covered the necessity of creating new dedicated teams to reduce the cognitive load on product teams. But we also identify signals for the opposite. Strong and exclusive dependencies between software components may indicate misplaced responsibilities. When communication overhead eclipses maintenance work, it may be advantageous to empower the consuming team to maintain the dependency.

Our software architecture evolves with our organization. The size and nature of our users influence how we provide our services. The number of employees in our company affects how we build software. We reflect changes to our software architecture and continuous delivery flow in our team constellation. "The architecture of the system gets cemented in the forms of the teams that develop it", Ruth Malan put it concretely.