Autonomous Team Structure

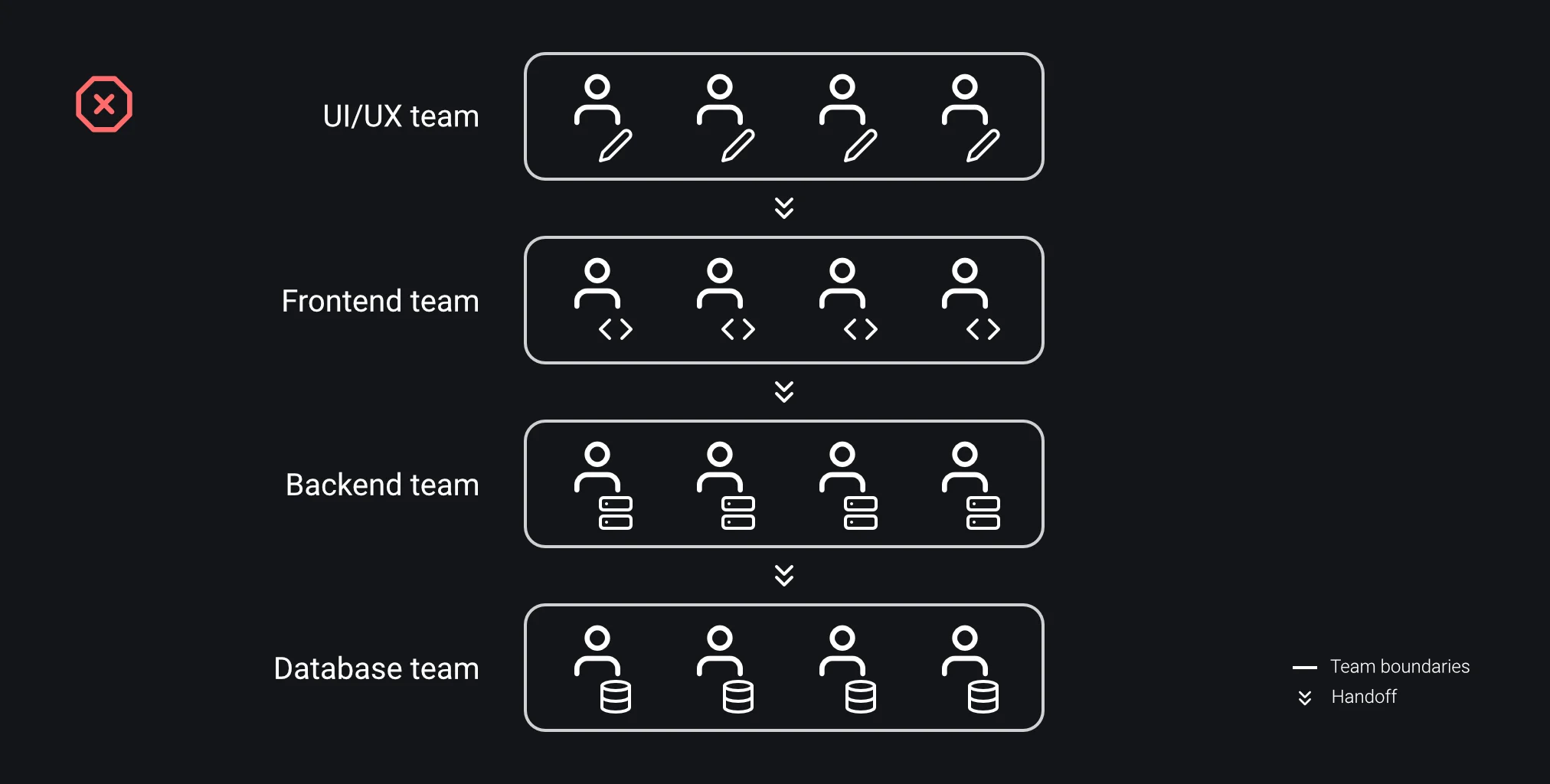

In early web development, teams were organized by discipline. The front-end department developed the visual interaction for websites, the back-end department worked on the system logic of input received from the user, and the database department managed data across user sessions.

Teams partitioned by discipline face multiple handoffs and extensive inter-team communication to deliver customer-facing features. This approach drastically reduces the velocity of releases and potentially introduces internal friction and an "us-vs-them" blame culture across teams.

The natural inertia within monodisciplinary teams directs our team toward misguided goals. A team consisting entirely of backend engineers will focus on building the best back-end system they can envision. While this might be an attractive and self-rewarding task for engineers, our organization requires our teams to focus on the best possible customer experience.

Vertical Teams

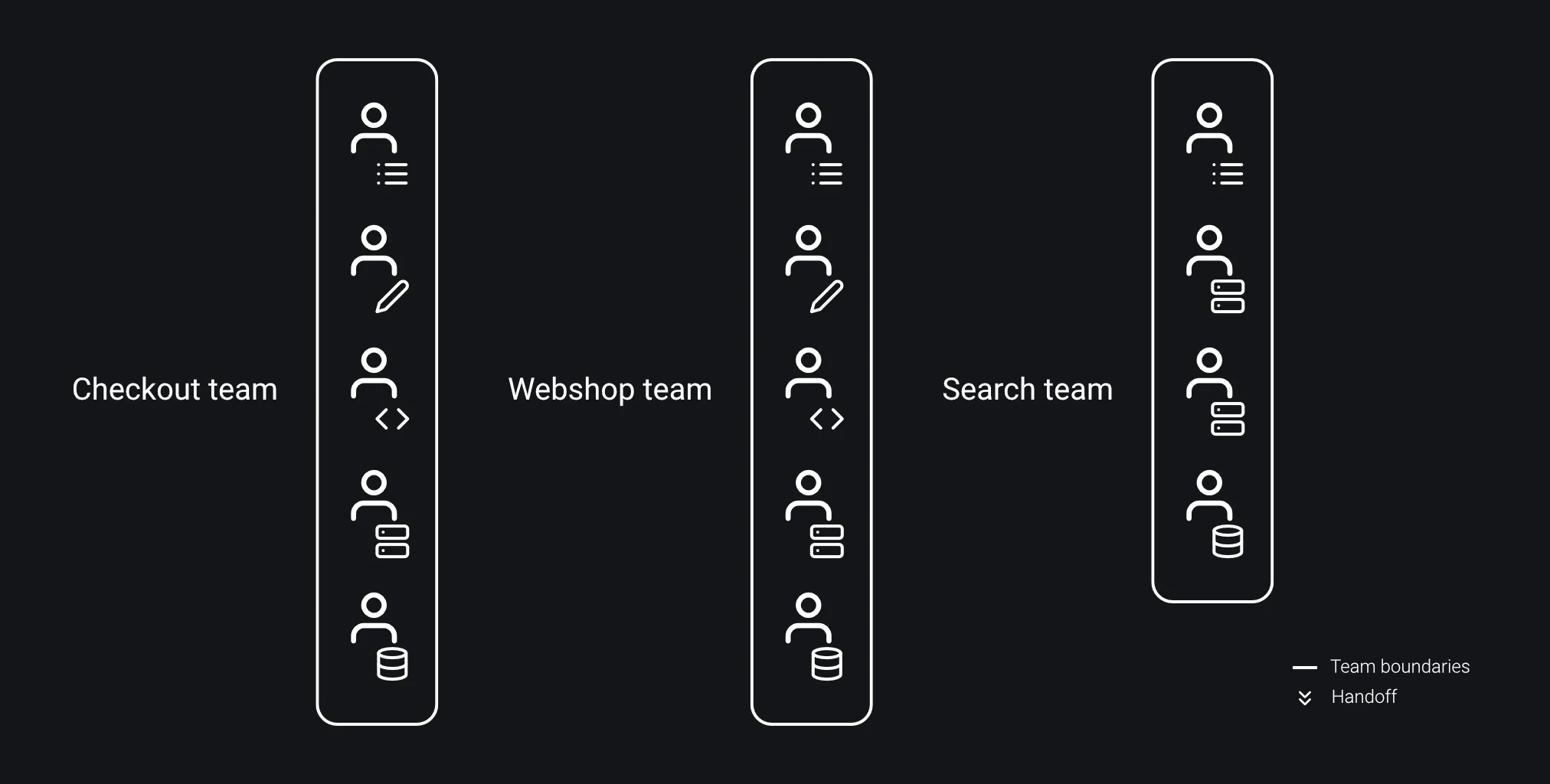

Designing teams as cross-disciplinary vertical structures allows us to align multiple competencies with a shared purpose. A vertical team focuses on a single service, feature, or user persona and is empowered to build and deliver customer value as quickly and independently as possible. The team doesn't require handoffs to other teams to perform parts of the task, which helps achieve rapid iteration cycles by working autonomously.

Vertical teams include all disciplines across the necessary tech stack. Typically, a vertical team has members versed in project management, security, infrastructure, development, metrics and monitoring, and UX. These disciplines aren’t a strict one-to-one mapping of skills to members; a member may cover multiple areas, and teams may require more or fewer disciplines depending on their needs.

The success of a vertical team lies in its ability to deliver changes to production without dependencies on other teams. It owns its tech stack and continuous delivery pipeline and can address newly discovered limitations or flaws in the system autonomously. This ensures a reliable feedback loop with customers and the ability to choose the most appropriate technology for a problem, e.g., using a document database or a graph database.

In 1955, Elting Morison published a study, "Mining Coal: How Long Can We Continue?", exploring team efficiencies in coal mines. The key findings emphasized the importance of team autonomy and self-management in improving productivity. The study showed that smaller teams tend to operate more efficiently because each member has a clearer understanding of their responsibilities and can coordinate efforts more effectively.

Before James P. Womack's "The Machine That Changed the World" popularized lean manufacturing, Womack worked as a project manager at Ford. His team visited the Toyota operations in Japan and were surprised to see how autonomously teams at Toyota operated on the production floor - a stark contrast to Ford's centralized decision-making and hierarchical structure.

Vertical teams were rediscovered in software development in the early 2010s. The book Team Topologies, a major influence on Engineering Collaboration, refers to vertical teams as stream-aligned teams and emphasizes the importance of autonomous delivery. Spotify popularized its organizational approach with The Spotify Model, which includes a multidisciplinary team composition called Squads. However, the vertical teams in Engineering Collaboration don't necessarily follow the same reporting schema or chapter structure as the Spotify model.

Team Size

Based on the behavior of primates, British anthropologist Robin Dunbar proposed that humans can comfortably maintain 150 active social contacts. This number represents our social outer circle, with smaller numbers as we approach our inner circle. According to the theory, we are capable of 50 meaningful relationships, share strong relationships with 15 people, and deeply trust 5 people. These numbers are subjective and vary by individual.

According to Dunbar's theory, a team should consist of three to nine people. Teams smaller than three may struggle with diverse responsibilities, while larger teams face communication overhead and accumulated noise. Amazon famously put it as "A team should be fed with two pizzas." - a unit of measurement that may work in the United States, but would starve any team larger than three in Europe.

We handle increased workload of the same nature by scaling up our team to the maximum of Dunbar's number. If the workload increases beyond this scope, we identify a separation of concerns within our software and split the team along this architecture. Teams adapt quickly to an increase in volume of similar work, but a more interesting challenge arises when complexity increases.

When working on problems, we have a limited capacity for the information we can hold in our minds. Most engineering work involves solving problems within a specific context. This context becomes increasingly complex with additional abstractions, user personas, and architectural demands. The larger and more complex a team's systems become, the greater the cognitive load required to effectively deliver results.

Besides the complexity of systems, context switches consume a large amount of cognitive load. When we work on a problem, we enter a focused state often referred to as the zone or a state of flow. In this state of heightened productivity, we lose ourselves in the task at hand and perform at peak efficiency. We reach the zone after fifteen to thirty minutes of uninterrupted focus. Every context switch pulls us out this state.

Because cognitive overload and context switching have such a detrimental effect on our productivity, it makes sense to split the team and assign dedicated responsibilities before reaching the upper limit of Dunbar's number.

Internal Supporting Teams

All teams within our organization are vertical, and most of our teams work on features for our customers. However, complex problems can be solved more efficiently by dedicated teams. These supporting teams reduce the burden on product teams by delivering software internally.

In the 2012 paper, A Taxonomy of Dependencies in Agile Software Development, Diane Strode and Sid Huff propose three different categories of dependencies: knowledge, task, and resource dependencies.

These were adapted by Matthew Skelton and Manuel Pais in the book Team Topologies. Based on the findings of the paper and their personal experience, the authors differentiate three types of supporting teams: complicated-subsystem teams, enabling teams, and platform teams.

Enabling Teams

Product teams inevitably encounter a problem that syphons focus from their work and reduces the frequency of product updates. A distracted product team makes our organization vulnerable to changing market demands. To remove the strain on their development velocity, we establish an enabling team. The newly formed group takes responsibility for the impeding issue and delivers usable solutions.

Enabling teams solve limitations of three kinds: problems of time, complexity, or magnitude. The first category - time - might be the most relatable experience. A team spends an unreasonable amount of time solving a tangential problem, hindering the team's primary responsibility of delivering features within its domain. We create an enabling team to take on the problem instead. The dedicated enabling team has the resources and cognitive load to deliver a sustainable solution to the initial team.

Problems of complexity grow over time. Once they reach a certain threshold, our engineers struggle to mentally retain the intricacies of a problem. One possible reason might be that our product evolved and the team's responsibility has become too broad. In that case, we reassess whether to split our team into multiple product teams.

Another cause of complexity originates from organic code growth leading to accumulated technical debt. Technical debt is the cost of doing business. As an organization, we prefer to deliver features fast and generate income as early as possible. The accumulated complexity results in opaque software architecture and convoluted code. An enabling team with domain expertise can identify the extent of the problem and implement a strategy to pay off our technical debt.

Problems of magnitude entail large-scale changes across our organization that require deep knowledge of a problem. Typical scenarios include regulatory compliance, uncovering security vulnerabilities, or comprehensive technical migration. For example, our organization decided to globally transition from Python 2 to version 3:

A dedicated enabling team researches the challenges of the migration and explores strategies to minimize disruptions for our workforce. The team writes migration guides, automation tooling, and provides testing suites. After the enabling team has solidified an approach, it collaborates with vertical teams across the organization to ensure a successful transition.

Enabling teams are temporary and focused on transferring knowledge, introducing capabilities, or solving singular problems. They aim to make product teams self-sufficient.

Complicated-Subsystem Teams

Hard problems are hard. This tautology is the driving force behind complicated-subsystem teams. If a problem requires highly specialized knowledge outside of our current team's domain, we hire dedicated personnel to own the problem. One example would be hiring computer graphics engineers to build 3D rendering solutions for our web teams.

Within Engineering Collaboration, we emphasize the importance of enabling our employees to learn new skills and grow in their careers. Complicated-subsystems are rarely such an opportunity. Typical complicated problems require higher education and experience in advanced physics, mathematics, and computer science.

The driving factor for complicated-subsystem teams is to reduce the cognitive load of a vertical team, not necessarily to share the component across multiple teams. Complicated-subsystem teams own the problem long-term and work on libraries that are then consumed by product teams.

Platform Teams

The larger our software product becomes, the greater the overlap of common challenges. Every team needs to build, test, and deploy software. Every team needs to gather crash reports, logs, and metrics. Every team needs to store, request, and back up data. To consolidate our approaches, we build internal platforms.

Platform teams are vertical teams that deliver features to an internal platform. Platform teams differ little from product teams. They are structured alike and use the same processes. As with our public software, an internal platform consists of multiple teams delivering different feature sets to the rostrum. And just like product teams, platform teams use the platform to build the platform.

Internal platforms provide services with self-service endpoints and configuration options to satisfy the product team's needs. The product teams maintain full ownership of building, testing, and deploying their applications to production. If their system breaks, it is the product team's (not the platform team's) responsibility to investigate and fix the problem. However, the platform must offer mature debugging tools and proper documentation for our product teams to do so.

Enabling teams and complicated-subsystem teams deliver solutions for one-off problems or to a single team. Through tight collaboration, these teams fine-tune the solutions to the specific product team's needs. Conversely, platforms serve the majority of our technology teams. As we cannot expect to onboard all teams in person, we mandate a strong focus on usability when developing our platform. Platforms offer a high level of documentation, a polished API experience, and dedicated contact channels for support requests.

Recommendation

In Team Topologies, IT consultants Matthew Skelton and Manuel Pais share secrets of successful team patterns and interactions to help product, technology, and engineering leaders design high-impact team-of-teams organizations. Engineering Collaboration covers some high-level concepts of Team Topologies.

For additional details and information, I highly recommend you check out the book and more at teamtopologies.com.

Team Topology Over Time

Team constellations are not static. We revisit our teams and their positioning with the adoption of additional technology, changing market practices, and an expanding internal skill set. Additional workload or cognitive load encourages us to split product teams. Barriers and distractions to development progress lead us to establish temporary enabling teams, permanent complicated-subsystem teams, or build an internal platform with platform teams.

Identifying and labeling internal supporting teams helps us recognize patterns. Technical debt, for example, can be paid with either team category. We decide which team to deploy depending on the scope and longevity of the solution. Visualizing the flow of software through supporting teams clarifies who a specific team's customer is. We then build inter-team interactions and communication channels to understand their needs.

Different industries require different compositions of internal supporting teams and product teams. The needs of a SaaS platform do not match the development practices of a AAA gaming studio. If any cross-industry axiom were to be found, it would be that the work of product teams generates revenue, the work of supporting teams reduces the cost of the former. We create and hire for internal supporting teams if and when we discern a fiscal advantage.

Further, we offer our platform and complicated-subsystem services to our product teams at cost. If product teams need to account for the cost of supporting teams in their budget, we can reason that only necessary technology survives within our organization. If a majority of product teams decide the benefit of a certain aspect of the platform is not worth the cost, we reconsider the benefits of maintaining it. Conversely, if we provide all services for "free", our organization may burn through significant capital for non-essential features.

The price barrier of internal tools allows us to identify effective opinions for further development. Actionable feedback originates from paying customers only. A wish list of nice-to-have features from non-paying users leads to bloated platforms with unnecessary features. As an organization, we want to mimic the free market consequences of poor product-market fit within our internal ecosystem - just a little less harshly.