Testing

Testing is a complex and divisive topic. If not done adequately for our use case, we are better off doing less of it. Zealously over-testing potentially ends up being as expensive as imprudently disregarding testing altogether.

This chapter covers what we have found to be generally most useful. Despite our good intentions, we do want to point out that testing is the least directly applicable undertaking from all recommendations in this book. Successful and sensible testing is modeled against our team's needs and evolves over time. We revisit our testing strategy periodically and after significant events.

Test-Driven Development

A term often cited in software engineering job listings is Test-Driven Development (TDD). TDD is the practice of writing tests for the behavior of a feature before working on the source code. An implementation is considered complete once it passes all tests and edge cases.

TDD encourages us to consider and transcribe a strategy to tackle problems in small increments. The upside of TDD sees diminishing returns with a growing complexity of implementations. Functions using file I/O or network I/O, or processes reliant on environment configurations are difficult to write tests for, even more so before the implementation is available.

The Testing Pyramid

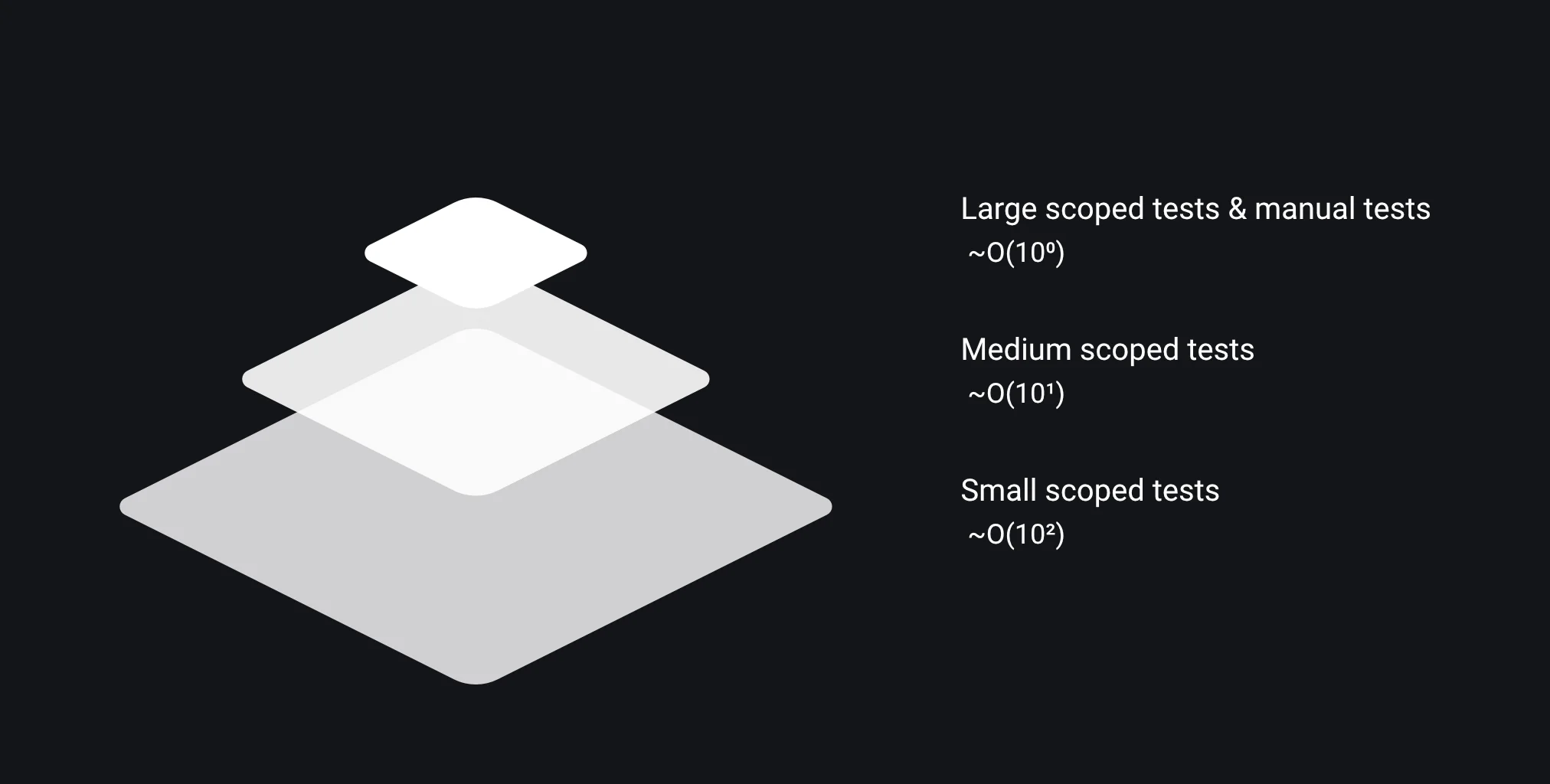

In the 2009 book "Succeeding with agile" Mike Cohn provides the metaphorical representation of the testing pyramid. The three-layered structure indicates guidelines for the amount of automated testing for each scope. The scope of the tests relates to the execution time and complexity of the test environment. The nature of these tests is outlined in detail in their individual chapters.

The base of the pyramid relies on numerous small-scoped unit tests that are run most frequently. Unit tests (Small-Scoped Tests) ensure correct behavior within a system.

The mid-layer consists of a reduced number of integration tests (Medium-Scoped Tests) ensuring correct behavior between embedded or connected systems.

The pinnacle of the pyramid consists of automated end-to-end tests (Large-Scoped Tests). These ensure correct behavior across the entire product and require complex setups and are generally long-running operations.

From bottom to top, every layer of the pyramid reduces the number of tests by an order of magnitude. If we have 1000 SST, we aim for 100 MST, and no more than 10 LST. A common anti-pattern is what we refer to as a test snow cone, or inverted pyramid. These projects contain little to no small-scoped tests with all the testing done in labor and time-intensive manual tests. The emerging results are slow test runs and long feedback cycles.

When to Test

Testing is not a one-off task done as a step in the waterfall methodology. Throughout the life of a code change, a varying suite of automated tests ensures the correct integration of code changes at different times. Tests are executed …

- … on our developers' machine during development;

- … on pull requests (Pre-merge);

- … after a merge into main (Post-merge);

- … periodically on the main branch;

- … when creating a release candidate (Pre-release);

- … against the live version of our software (Post-release).

For every step, we provide context as to why that particular constraint exists to make it feel less arbitrary. People are less inclined to push back against rules when there is a clear reason behind them.

Hermetic Environments

Tests run on various machines and runners, by various users and scripts, on various operating systems and environments. Failing tests due to drifting environmental configurations hinder development and build resentment towards writing and executing tests in the first place.

A hard requirement for tests is to be hermetic, meaning not reliant on a specific environment or execution order to be successful. Tests set up, execute, and tear down independently and in a confined manner. Tests provide accurate information regardless of the order in which they are run.

Medium and large-scoped tests provide the environment and infrastructure needed to execute expectedly. Using container tools such as Docker and Infrastructure as Code (*WIP) (IaC) workflows ensures consistent configuration across platforms and machines. Small-scoped tests run without requiring a dedicated hermetic environment. Our testing suite performs as intended on every machine regardless of environmental configurations. As developers, we are able to replicate failing tests on the CI/CD runners on our machines.

Testing over Time

The most important property of our testing suite is our developers' trust in the process. The rare superlative is warranted, and we elevate the former statement to our absolute priority. We add tests when bugs are reported. We remove tests when they become brittle, flaky, redundant, or even just inconvenient. We move tests to be executed at different times when the current setup proves inefficient or ineffective. The following statements are red flags to be addressed:

"All tests passed, except for Test A. That one fails about 60% of the time, though, so I'm ignoring it."

Brittle tests normalize the tendency of ignoring failed tests. Introducing that mindset turns our product testing into an expensive waste of time instead of a useful tool of shifting left.

"That test takes about twenty minutes, just merge the code now. We don't have time for this!"

We remove the test should it not provide the appropriate value. Twenty minutes is a long time to occupy machines that may be better suited for other jobs. If the test is necessary, we consider shifting it right, e.g., from pre-merge to post-merge.

"Every time I touch that function, the tests fail; it's a huge pain in the ass!"

See if we can test a higher layer of abstraction of the functionality. If not, we throw it away. The utmost priority is for developers to actively use the automated test suite and not build resentment towards the process.

Tests as Documentation

Software documentation is notoriously unreliable and commonly has a tenuous relationship with the realities of the code it references. Written documentation about the behavior of edge cases or default return values is not to be trusted. No matter the extent of the drift, documentation still "functions". Tests break.

Clear and focused tests provide context as to the purpose and limitations of code segments. Tests of edge cases demonstrate expected behavior for teams consuming our code. Demonstrated expected behavior streamlines pull requests, as code reviewers spend less manual effort verifying code correctness.

Who writes Tests?

Some languages come with native testing tools, others require frameworks and external dependencies to execute test code. Factor in that different testing stages typically have different requirements, and we are faced with quite a collection of tools. It is reasonable to assign the selection, maintenance, or development of test tooling to dedicated teams.

It is not reasonable, in fact, it is highly discouraged, to move the responsibility of writing and executing the tests away from the developer writing the functionality. This change is sometimes introduced when the complexity of testing increases, such as end-to-end tests involving UI, middleware, backend services, and database entries. In order to reduce cycle times, it is imperative that developers write and maintain the tests.