Merging

Depending on the discipline, the concept of repository streams, and branch isolation, merging changes differs between version control solutions. Universally, we discuss the idea of re-integrating changes into our main software product or uniting changes of differing origins.

Note

Since merging varies between tooling, we focus on the practices within Git. This chapter is one of the rare exceptions that includes technical commands and ties to a specific platform.

Git includes various strategies for converging changes to a single destination branch. Ungoverned, our project might grow in unnecessary complexity, include opaque processes, or lose information relevant for future fixes. This chapter details merging policies for successful long-term integrations in trunk-based development.

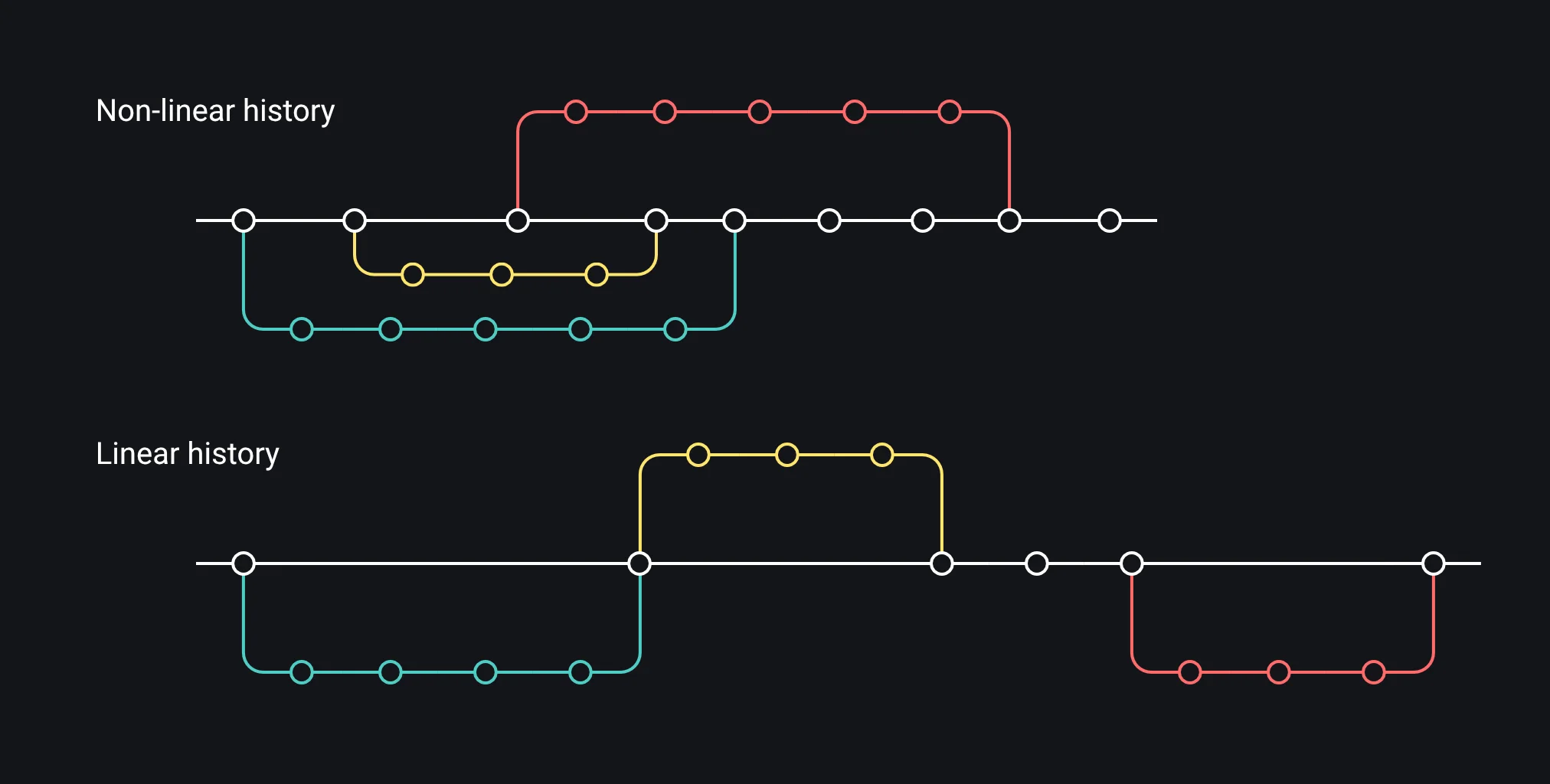

Linear History

Regardless of our approach, when merging changes into software, we ensure a linear history of our project. The parent commit of our development branch is the latest commit on main. A linear history sequentially chronicles the evolution of our software and streamlines future reactionary development.

Sometimes, we introduce unexpected breaking changes. A non-linear history complicates identifying and reverting an offending commit. If left unattended, a non-linear history breaches the point of illegibility and emerges as being utterly useless. Future bug fixes and tracking changes over a period of time devolve into frustratingly hair-pulling endeavors.

Rebase

We sprouted our development branch off the latest commit of the main when sowing the seeds of our work. Chances are, while developing our feature, our colleagues integrated their tasks into the main branch, thus putting us in the position of cultivating a non-linear history should we merge our botanical offshoot into the trunk unchanged.

In order to rectify our entanglement, we rebase our work on the latest commit on main, fix occurring conflicts, and integrate our changes after passing our automated test suite. A rebase precedes any merge into our main branch.

Note

When rebasing a branch, we create new commits on our local machine that no longer mirror the state of our remote repository. We either force-push (with-lease) our changes, overriding the state of the remote repository, or create a new branch from the head of our development branch and rebase and push that one, abandoning our development branch. We do so with the respect and caution required when rewriting project history in a collaborative environment.

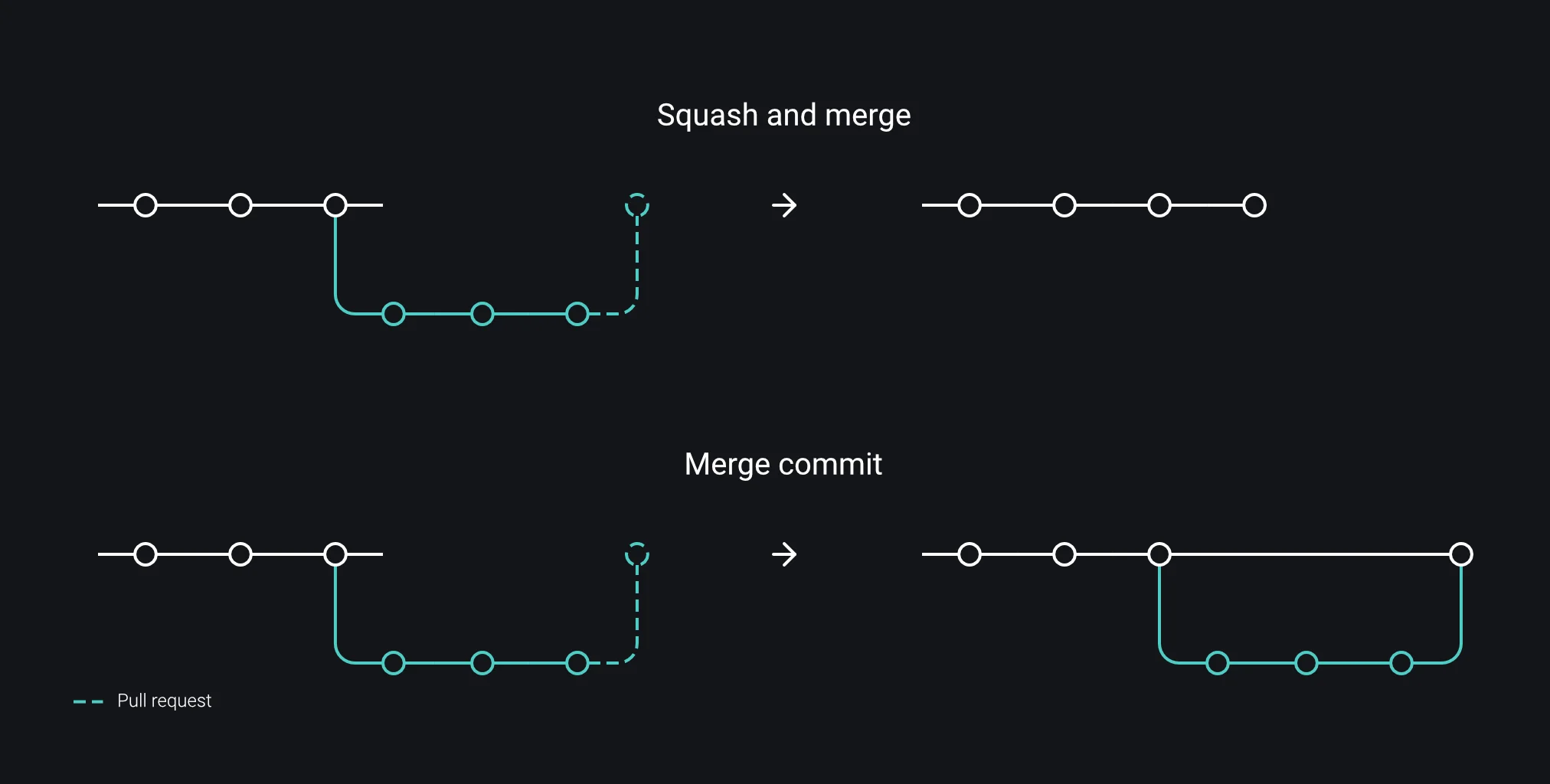

Squash and Merge

Squashing an arbitrary number of consecutive commits combines and replaces those changes into a single commit. By consolidating work-in-progress commits or bilaterally annulling commits, we reduce noise in our project history.

Most source control platforms offer the option of a server-side Squash and Merge approach when integrating changes of a completed pull request (PR). The procedure squashes all commits of our development branch and appends our changes to the main branch as a single commit.

For short-lived development branches focusing on fixing or adding a single responsibility, the development steps are less important than the changes themselves, and the commits may be squashed and merged. Complex issues are documented as inline comments or within the PR description.

With a hypothetical average of ten commits per development branch, by squashing, we reduce the growth of commits over time from 10,000 commits to 1,000 commits.

Merge Commit

On occasion, the complexity of achieving a task or the volume of changes across multiple files requires chronological cataloging for transparency. Merge commits allow us to preserve the development commits we created within the repository without clobbering the main branch.

The particular branching view of a merge commit allows us to either ignore the development commits when analyzing the main branch via git log or git bisect, or step into them if we are interested in the history of the changes.

This GitHub blog article details practices for advanced users of Git about structuring a story of our commits when merging our work via a merge commit. The well-written paper outlines how thematically organized commits increase the readability of changes by spanning the dramatic arc of our development process; from partial implementations to tests, refactors, polish, and documentation.

Cherry-Picking

The act of cherry-picking commits cannot, in good conscience, be described as a merge. It is, however, an additional way of transferring select commits between branches. The command git cherry-pick allows us to append an existing commit to our current HEAD.

Optionally, cherry-picking applies the contents of a commit to our current workspace, rather than appending a commit itself. This permits us to edit the content or revert unwanted modifications bundled within the cherry-picked change before creating a new commit in our development branch.

Resolving Conflicts

Git merges compatible changes automatically. Resolving conflicts, however, requires manual intervention. We compare the clashing lines of changes and rectify the discord by editing the changes to accept a change from either source or manually edit a functioning resolution containing workings of both origins.

When rebasing changes, we find ourselves recurrently resolving the same lines across commits; such is the nature of this process. We minimize our rebasing effort by integrating changes frequently into main, rebasing our development branch frequently, squashing development commits of our development branch.